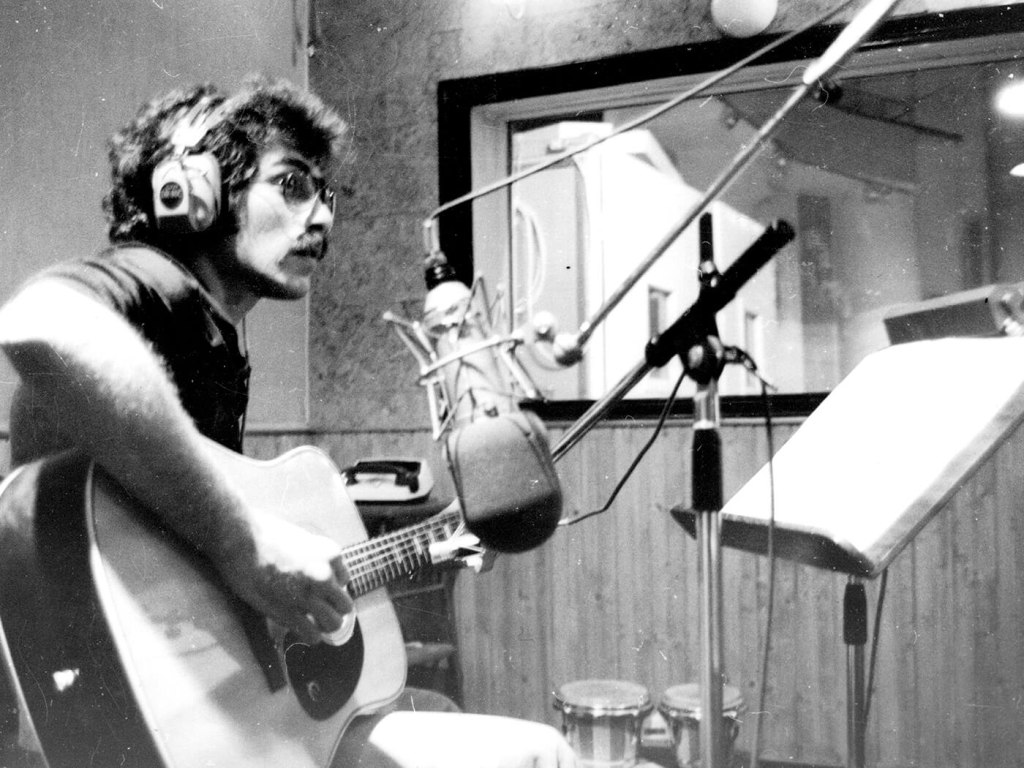

A time machine in human form, Lebanese musician Roger Fakhr will have you walking in the streets of Beirut in the 1970s, from the comfort of your couch in Montreal.

Of all the places Fakhr has had the pleasure and chance to visit as an artist, it seems the past is one of his favourites.

As he mentally skims through the landmarks and time stamps that made him the man he is today, I sit there, blissfully unaware of the time passing, feeling as though I have stepped into a time before my parents even met.

We’ve been surrounded by recollections of the past from European and American artists of the 1960s, and 1970s. I’ve listened to friends romanticize those decades and feel a connection to bands from that time that I’ve strived to familiarise myself with – and to a certain extent, I truly believed I was able to. But they had a cultural connection to bands like The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and even Led Zeppelin that I would never have.

And all of this dawned on me as I listened to the legendary Roger Fakhr speak – speak of a world familiar to me. A shared love for a country we both moved away from, but keep close to our hearts wherever we go.

Fakhr spoke of his experiences, strolling down streets I’ve walked many times, of artists I’ve listened to with my mother, as if he could still smell the rain that fell on the tarmac on cold winter months, or hear which chords they switched around with in the studio.

“Today the songs are just, it’s like they don’t go anywhere, you know?” Fakhr says. “And you have to be a clown on stage. You have to have those big shows with fireworks, and you have to dance. The actual value of a song is not the same today as it used to be in those days. So we were very lucky [to live in those times.]”

Roger Fakhr’s journey to the pursuit of Folk stardom was as rocky as every folk road. For starters, the artistic life was not something his parents supported.

“When I was 17, I was supposed to be part of a concert in Beirut,” Fakhr recounts. “My band and I were getting ready for the show, but my dad didn’t want me to play. Because I wasn’t doing well at school. So, I got really upset, I packed my bags, and I left, which is something you don’t do in Lebanon.”

Young Fakhr found a friend in James Taylor, and saw his whole life paved for him – a life worth defying his parents for.

“When I heard the guitar in “You’ve Got a Friend in Me,” I just fell in love,” he says, “and I said, that’s what I wanna do. I just wanna play guitar and sing a song, be a singer/songwriter, and then have a little band accompanying me.”

And so his youth was spent on the road most of the time, traveling to various camping grounds and different cities in Lebanon. That’s when he encountered different musicians and came across different types of music, seeking people who played guitar better than him in order to learn from them.

One of the most pivotal moment of Fakhr’s life was the serendipitous meeting with Lebanese jazz musician, Issam Hajali.

Hajali is probably best known for his work with the Lebanese collective Ferkat Al Ard, a Lebanese band that emerged in the mid 1970s. The band consisted of Hajali on vocals and guitar, Elie Saba on bouzouki and oud, and Toufic Farroukh on saxophone and flute. Their songs on Oghniya were primarily composed by Lebanese legend, Ziad Al-Rahbani.

However, Fekrat Al Ard was not Hajali’s first toe-dip into the Lebanese music scene. In 1977, he released Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard (‘Journey to Another World’), an album on which Fakhr was a big collaborator.

Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard was recorded in Paris, after Hajali fled Lebanon in 1976, due to his left-wing political leanings and support of the Palestine Liberation Organisation.

“Back then,” Fakhr says, “we didn’t even write sheet music. I didn’t know how to write sheet music, so we used colour pens. To decide. Okay. The yellow is the drums and this is where it comes in. The red is the electric guitar, the green is acoustic guitar, and we recorded the album.”

That’s how part of Fakhr’s famous album, Fine Anyway, also came to be.

Fakhr humbly keeps stating that most songs on the album are pretty short, explaining that he never had the chance to rework and develop them as they should be.

But one could argue that the “incomplete” feel of this album is a perfect expression of what Fakhr tried to convey in his songs; that things aren’t always in your control, and sometimes slip through your fingers.

In a 2021 interview with Test Pressing magazine, he confides in Martyn Pepperell that the Lebanese Civil War that erupted in the 1970s affected his work.

“Something was happening in Lebanon in the early ’70s. We were starting to sprout, you know, we were just starting to come up,” Fakhr says. “It was really a great time to live in Lebanon. When the war started, it was like, you know, somebody cut our throats or something. We just couldn’t continue and something died.”

He recorded parts of Fine Anyway in Beirut in 1977, and completed it in Paris in 1978, before growing tired of the winters in France and missing the warmth Beirut provided – in all its seasons. A warmth and comfort that his father, whose house Fakhr had run away from, provided for him upon his return, in a quaint house near the bustling Hamra Street.

This house became the headquarters for many musicians. Hajali and Fakhr’s friendship solidified further during that time, with Toufic Farroukh completing the trio.

Farroukh is a renowned talented saxophone player, living in France, known for singles like “A Night in Damascus” and albums such as Drab Zeen.

Fakhr’s friendship with Hajali led to him meeting one of Lebanon’s musical geniuses, Ziad Al-Rahbani.

Fakhr and Al-Rahbani bonded over their shared love for Brazilian guitar composition (Bossa Nova), something that influenced both their work. However, there was only one person calling the shots in the collaboration.

“Ziad also had his own agenda, and he was in a position or situation where he didn’t really need people to be with him,” Fakhr says. “He writes all his music and then he invites musicians to come.”

Al-Rahbani invited Fakhr to join his jam sessions after listening to a Fine Anyway cassette and being impressed with Fakhr’s talent.

“It was always, me as a musician doing what [Ziad] said he wanted on his albums to the extent that I could because I didn’t read music,” Fakhr says. “And that was a big gap between us because [Ziad] was very fast. He is a very fast, very clever musician, extremely versatile. A genius of politics and social issues. And I was in my little folk world, which was completely different.”

Fakhr speaks of Al-Rahbani with admiration, and respect. As he navigates through his past, he goes on to recount the time he was invited to tour the United States in 1979 with the Lebanese icon, and mother to Ziad, Fairuz.

“I immediately said yes,” Fakhr says. “My dream back then was to come to the U.S. and meet James Taylor. I was 20 years old. And so I practiced with the band and did the tour. It was a huge orchestra. It was like 80, 85 people, dancers, musicians, dabke group. It was a huge show and we were there, Abood, Walid, Toufic [Farroukh] and myself, and we were like the Western section of the orchestra. We were the drums, electric guitar. The other musicians were like, what is this? You know? But that’s art. That’s, that’s how [Ziad] does it.”

His experience in the U.S. is in clear contrast with the one he had in Norway in December of 1977.

“I lasted six months,” Fakhr says. “It was a great experience. The country is beautiful over there. It was a completely different experience to play with the band and be a singer. But unfortunately all they played was top 40, which was in those days “Stayin’ Alive” (The Bee Gees) and “I Will Survive” (Gloria Gaynor). I hated every minute of it, having to smile and dance and sing. That’s not at all what I wanna do in music. I’d rather not make money and, and continue to write songs as they come. So I left up six months, and went back to Lebanon.”

One cannot help but listen in awe at soft-spoken Fakhr as he expresses his love and passion for music. In a world nowadays where people sacrifice art and authenticity for security and wealth, his love for the written words and the simplicity of guitar strings led him to take all kinds of risks in his youth.

After finishing up the tour, Fakhr decided to stay in the U.S. and have a go at the American music scene – to quickly discover it was not easy at all.

“I found out that [the U.S.] was a completely different game,” he says. “There are zillions of great musicians and great singers in the U.S. It’s not like Beirut, where it’s small, and your friends know you and they all come to your concert. The cutthroat life of the music business I had to face. And mind you I tried, I had tried in Paris to go to record companies and send my tapes and all this. But it wasn’t the right time. It was the early eighties and nobody was interested in folk singing in the eighties.”

In spite of the curve balls, the music never stopped coming.

“I kept following music and I kept playing, but on my own, in the kitchen and living room and in the bedroom,” Fakhr says. “I bought a fourth track cassette tape and started recording. The old songs were there, but there was still new stuff coming and I had to put it down somewhere. So I have a bunch of this music sitting, waiting and it’s accumulated over the years and until today, it keeps continuing. So I kept recording to keep those things alive. But I never tried to perform, because I felt my songs were not ready, and I wanted to develop them more.”

It seems to be a constant pattern of Fakhr’s, to continuously question and doubt his work, holding off publishing them.

Fine Anyway was pressed and printed on barely 200 cassettes at the time of its completion, given exclusively to friends and acquaintances. So how did German record label, Habibi Funk, get a hold of it?

“[When I was first approached] I said, no way, forget it,” Fakhr laughs. “For over three years, we kept going back and forth and I kept saying, oh, I have to rerecord those songs. I have to develop them. They’re too short. There’s nothing there, there are no instruments. It was recorded very quickly.”

Fakhr tried to re-record the songs to at least have something clean cut to give to Habibi Funk, but founder Jannis Stürtz wasn’t having it.

“[Jannis Stürtz] wanted the original in lo-fi to show the spirit of the seventies. So he kept insisting that he wanted the song as is. He kept saying that new versions didn’t have the same feeling.”

The back-and-forth ended after the Beirut Port Explosion of August 4th, 2020.

“Jannis contacts me and says, well, I’m putting together an album to raise funds for the Lebanese Red Cross. Would you like to contribute two songs? And I said, yeah, sure. Let me check which ones.” Fakhr says. “Once the album was released, I said, okay, well two of my songs are out [of] the way with all their mistakes and all their issues and the fact that I don’t like them, so why don’t we just go for it?”

And so, in 2021, Habibi Funk Records released Fine Anyway, inciting great public response.

“It felt really, really nice that people liked the music the way it is, without embellishments,” Fakhr says. “I know that if this had been released years earlier, it would’ve never picked up the same. I don’t know how the timing was was very nice. People were ready for these kinds of songs because people were craving authenticity.”

In addition to being authentic and real, Fakhr’s art also relates to the youth for its political and social nature – no matter how subtle.

“I’ve always been affected and impacted by what’s happening in Palestine and in Lebanon, always.” Fakhr says. “Lebanon is, is me. It’s something you carry with you and try to spread. That’s what Lebanon is all about. I don’t have any songs written for somebody who left me. Most of the songs are more human, you know, it’s like they have to do the human feeling and what we go through as, as people, as humans.”

Roger Fakhr is currently touring European cities with co-headiner Charif Megarbane, Lebanese producer, composer, and multi-instrumentalist. Fingers crossed the Lebanese North-American diaspora gets to see this living legend live really soon.

Leave a comment